English

English

French

French

Factors associated with lung function impairment in subjects with past history of drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis in Cameroon

Facteurs associés à l'altération de la fonction pulmonaire chez les sujets ayant des antécédents de tuberculose pulmonaire sensible aux médicaments au Cameroun

Ngah Komo Marie Elisabeth1,2, Massongo Massongo1,2, Ntyo’o-Nkoumou Arnaud1,4, Amadou Dodo Balkissou3, Kuaban Alain1,2, Nsounfon Abdou1,5, Poka - Mayap Virginie1,2, Ngadi Patience2, Endale Mireille6, Pefura - Yone Eric Walter1,2

1Department of Internal Medicine and Specialties, FMBS, University of Yaoundé I, Cameroon.

2Pulmonology Service, Jamot Hospital, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

3Department of Traditional Medicine and Pharmacopoeia, FMBS, University of Garoua, Cameroon.

4Pulmonology Service, Garoua Military Hospital, Cameroon.

5Internal Medicine Service, Yaounde Central Hospital, Cameroon.

6Laquintinie Hospital, Douala, Cameroon.

Corresponding author: Ngah Komo Marie Elisabeth. Department of Internal Medicine and Specialties, FMBS, University of Yaoundé I, Cameroon.

Email: elisabeth.ngah@fmsb-uy1.cm

ABSTRACT

Background: Despite achieving microbiological cure following pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) treatment, a substantial proportion of patients’ experience persistent lung function impairment (LFI), which may alter their long-term respiratory health and quality of life. This study aimed to identify risk factors associated with LFI in individuals with a history of successfully treated PTB within a community-based setting.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was part of a large-scale community survey conducted in five regions of Cameroon (Yaoundé, Douala, Bandjoun, Garoua, and Figuil) between 2014 and 2018. Individuals aged 19 years or older were included, with documented prior successful PTB treatment and valid pulmonary function test results. Demographic, clinical and spirometric data were collected. LFI was defined as a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁) below the lower limit of normal (LLN). The log-binomial regression model was used to identify factors independently associated with impaired lung function and statistical significance was set at p< 0.05.

Results: Of the 135 participants included, 70 (51.9%) were male and 70 (51.9%) aged between 40 and 59 years[A1]. Low socioeconomic status was found in 52 (38.5%) of participants, 95 (70.4%) were non-smokers and 63 (46.7%) had a normal body mass. The prevalence of LFI was 31.9% (95%CI), with 58.1% classified as mild and 37.2% as moderate. Independent factors associated with LFI included informal employment (aOR = 3.0(95%CI), p = 0.028), current smoking (aOR = 3.6

(95%CI), p = 0.021), and exposure to firewood smoke (aOR = 17.7(95%CI), p = 0.008). Conclusion: One third of patients successfully treated for PTB have an impairment of pulmonary. Informal employment, current smoking, and exposure to firewood smoke were significant associated factors with LFI. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions to mitigate long-term respiratory sequelae in post-TB populations.

KEYWORDS: Lung function impairment; post-tuberculosis lung disease; spirometry; Cameroon.

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte: Malgré l’obtention d’une guérison microbiologique après le traitement de la tuberculose pulmonaire (TP), une proportion importante de patients présente une altération persistante de la fonction respiratoire (LFI), susceptible de compromettre leur santé respiratoire à long terme et leur qualité de vie. Cette étude avait pour objectif d’identifier les facteurs de risque associés à la LFI chez des individus ayant des antécédents de TP sensible aux médicaments, traitée avec succès, dans un contexte communautaire.

Méthodes: Il s’agit d’une étude transversale intégrée dans une enquête communautaire à grande échelle menée dans cinq régions du Cameroun (Yaoundé, Douala, Bandjoun, Garoua et Figuil) entre 2014 et 2018. Les individus âgés de 19 ans ou plus, ayant une preuve documentée de traitement antérieur de TP réussi et des résultats valides d’explorations fonctionnelles respiratoires, ont été inclus. Les données démographiques, cliniques et spirométriques ont été collectées. La LFI était définie par un volume expiratoire forcé en une seconde (VEMS) inférieur à la limite inférieure de la normale (LLN). Un modèle de régression log-binomiale a été utilisé pour identifier les facteurs indépendamment associés à l’altération de la fonction pulmonaire, avec un seuil de signification statistique fixé à p < 0,05.

Résultats: Parmi les 135 participants inclus, 70 (51,9 %) étaient des hommes, et 70 (51,9 %) étaient âgés de 40 à 59 ans. Un faible statut socio-économique a été retrouvé chez 52 participants (38,5 %), 95 (70,4 %) étaient des non-fumeurs et 63 (46,7 %) avaient une masse corporelle normale. La prévalence de la LFI était de 31,9 % (IC95 %), dont 58,1 % classés comme légère et 37,2 % comme modérée. Les facteurs indépendants associés à la LFI comprenaient l’emploi informel (aOR = 3,0 (IC95 %), p = 0,028), le tabagisme actuel (aOR = 3,6 (IC95 %), p = 0,021) et l’exposition à la fumée de bois de chauffe (aOR = 17,7 (IC95 %), p = 0,008).

Conclusion: Un tiers des patients traités avec succès pour une TP présentent une altération de la fonction pulmonaire. L’emploi informel, le tabagisme actuel et l’exposition à la fumée de bois de chauffe sont des facteurs significativement associés à la LFI. Ces résultats soulignent la nécessité de mettre en place des interventions ciblées pour réduire les séquelles respiratoires à long terme chez les populations post-TB.

MOTS CLÉS: Altération de la fonction pulmonaire; maladie pulmonaire post-tuberculeuse; spirométrie; Cameroun.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major public health concern, ranking first among single-agent infectious diseases in terms of morbidity and mortality, ahead of HIV/AIDS [1]. The implementation of programs that promote early detection and enhanced treatment of patients led to a decrease in the annual incidence of TB from 309 cases per 100,000 people in the year 2000 to 179 cases per 100,000 people in 2019 [2]. The pulmonary forms of TB continued to be the most prevalent type. In the majority of cases of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), microbiological healing occurs. However, this does not signal the end of the illness. When TB invades the lung tissue, it can result in both structural and functional alterations [3]. These modifications include emphysematous changes, pulmonary fibrosis, bronchial distortion, and bronchiectasis, all of which can lead to impaired lung function [4]. This subsequent long-term impairment of lung function contributes to the long-term morbidity and mortality of these patients, as well as substantial costs for the health system [5]. The prevalence of lung function impairment (LFI) among individuals who have completed PTB treatment, as reported in various studies, ranges from 10% to 45.4% [6, 7]. The majority of these studies have been conducted in Latin America and Asia. However, we discovered just one African study, which was limited to a specific group in South Africa [2]. Furthermore, little information exists regarding the factors that contribute to LFI in successfully treated pulmonary tuberculosis patients in our country. Therefore, this study was conducted in order to identify these factors, which may help prevent LFI or provide closer monitoring of high-risk patients.

METHODS

Study design, setting and population

The present cross-sectional study originated from a large community survey conducted in five areas of Cameroon: two urban (Yaoundé and Douala), two semi-urban (Garoua and Bandjoun) and one rural (Figuil) between 2014 and 2018. We enrolled adults aged 19 or older using a 3-tage cluster multi-stratified random sampling. Our research focused on individuals in a recent community respiratory health survey, specifically those who successfully underwent trea ment for pulmonary tuberculosis. We chose participants from the subset of respondents (5055) who completed a valid spirometry test. For our study, we calculated our required sample size with the stat calc tool of Open Epi version 3.01 (Open-Source Statistics Epidemiology for Public Health), using a dedicated formula for population surveys. We considered a 95% confidence Interval, 45,4% expected prevalence found by Mbatchou Ngahane et al in Douala (Cameroon) [7], a 1% margin of error. The obtained sample size was 354.

From this community survey, 135 participants had a documented history of successfully treated pulmonary tuberculosis. Also, we excluded participants who had undergone treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, as well as those with a history of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Study procedure

The data were collected by seventh-year undergraduate medical students during in-person conversations using a questionnaire, who had been trained in spirometry. At the Jamot Hospital for 06 months and supervised by a pulmonologist. Subsequently, the students input the data into a computer using the Epi Data entry 3.1 manager software (Epidata Association, Odense, Denmark). Each qualified individual was meticulously documented based on various criteria: their age, gender, profession, socioeconomic background, marital status, previous health conditions such as HIV, respiratory infections like pneumonia, cigarette smoking habits, exposure to smoke from burning wood or coal, height (in meters) and weight (in kilograms), which were then utilized to compute their body mass index. Additionally, pulmonary function tests, specifically spirometry, were also collected. The socio-economic level was measured using the wealth index for Cameroon developed by the World Bank. A score was assigned to each wellbeing index (household appliances, ownership of a domestic, main source of drinking water, main fuel used, house flooring materials, number of people per bedroom). The wealth index is calculated using the formula: ∑si + [(number of persons per bedroom – 1.84)/1.27] – 0.0014 With ∑si = sum of individual scores for each item excluding number of people per room. Thus, poor subjects were those in the 1st and 2nd quintile of the wealth index, middle-income subjects those in the 3rd and 4th quintile of the wealth index, and rich subjects those in the 5th quintile. [9] It was categorized as low, medium, or high. The participants’ smoking habits were categorized into three groups: “current smokers” (those who consumed at least one cigarette daily for at least a year or had smoked at least 20 cigarettes in their lifetime and continued to smoke), “former smokers” (individuals who had quit smoking for at least six months), and “non-smokers” (people who had never smoked more than 20 cigarettes in their lives). Biomass fuel exposure was defined by the use for more than 6 months of either coal, charcoal, wood (logs or chips), sawdust, dung, or crop residues for heating or cooking purposes [12]. The height was measured by a wooden measuring board of local manufacture graduated in centimeters, and the weight by an electronic weighing scale. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kg)/height2 (in m2) and used to divide the study population into 4 weight categories: lean (BMI < 18), normal (BMI ≥ 18 and <25), overweight (BMI ≥ 25 and <30), and obese (BMI ≥ 30). Spirometry was performed with the participant in a seated position, as per the standard, using a turbine pneumotachograph (Spiro USB, Care Fusion, Yorba Linda, USA) in accordance with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society 2005 standards [8]. The technicians, who had extensive expertise and experience, carried out the test, and the ATS/ERS guidelines for acceptability and reproducibility were followed [8]. To establish a forced vital capacity (FVC) curve, each participant was required to undergo at least three, and no more than eight, tests with a minimum rest period of one minute between each one. The best of three tests that met the acceptability criteria were retained for each participant Spirometry’s variable of interest was the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). The values for the spirometry parameter were determined by estimating the predicted results and lower limit of normal (LLN) based on the Global Lung Initiative (GLI) 2012 reference values [10]. A person was considered to have lung function impairment if their FEV1 was below the LLN. The obstructive ventilatory pattern was defined by a FVC above the lower limit of normal and a FEV1 to FVC ratio below the lower limit of normal. The restrictive ventilatory pattern was defined by a FVC below the lower limit of normal and a FEV1 to FVC ratio above the limit of normal. The mixed ventilatory pattern was defined by a FVC below the lower limit of normal and a FEV1 to FCV ration below the limit of normal. The severity of LFI was graded using the Z-score of the predicted FEV1 as described by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). The Z-score was classified as normal (z-score>-1.645), mild (-1.65<z-score<-2.5), moderate (-2.5<z-score<-4), and severe (z-score<-4) [13].

Data management and analysis

Before exporting the data to the SPSS-IBM software version 23 (IBM, Chicago, USA), we made sure that there were no missing values. Qualitative data were summarized as percentages, while quantitative data were summarized as the mean ± standard deviation or as the median with the interquartile range. We used the Chi-square or Fischer’s exact tests to compare proportions and the student’s t test or its non-parametric equivalent to compare means. The log-binomial regression model was used to identify factors independently associated with impaired lung function. The strength of the association was estimated by the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The significance threshold was set at 5%.

Ethical and administrative procedures

In each region, an ethical clearance was obtained from regional delegation Results

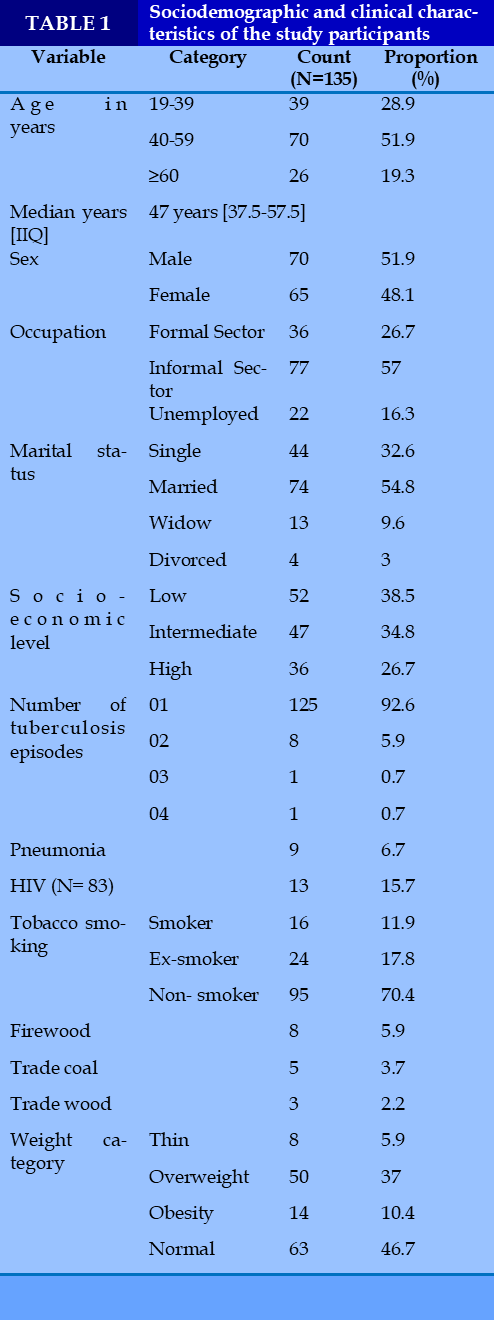

Baseline characteristics of study population

A total of 135 participants, with 51.9% being male. The median age (IIQ) was 47 [37.5-57.5] years, and over half (51.9%) were aged 40–59. According to social data, married individuals (54.8%), those from low socio-economic backgrounds (38.5%) and no-smoker (70,4%) were the most represented. In terms of weight category, normal body mass index accounted for 46.7%. In most cases, participants reported having experienced a single episode of pulmonary tuberculosis (92.6%). (Table 1).

Spirometric data

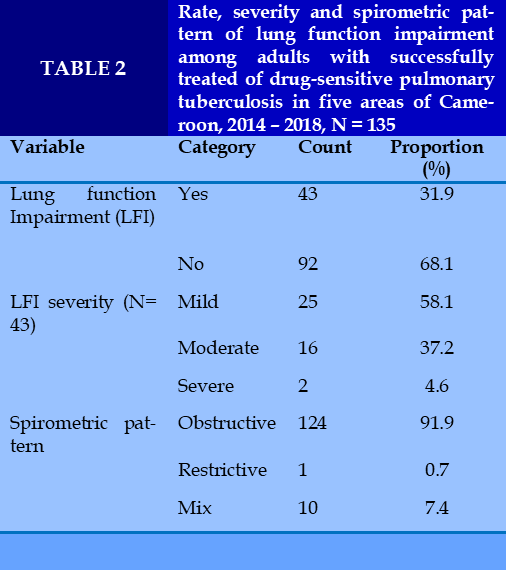

LFI was found in 31.9% [CI 95%: 24-40] of participants, with most cases being mild (58.1%) to moderate (37.2%).

Spirometric pattern, we have 91.9% obstructive pattern; 37.2% restrictive pattern and 4.6% mixed pattern (Table 2).

Factors associated with LFI

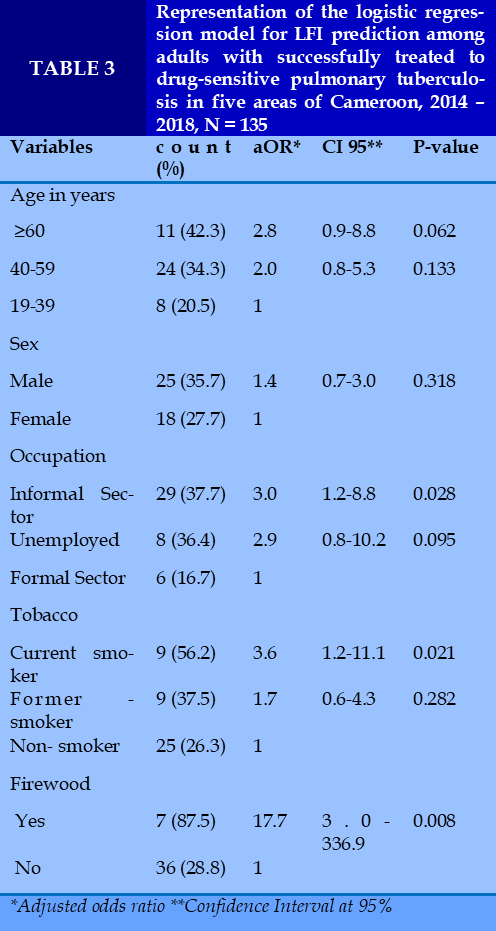

After conducting a univariate analysis, the occupations of individuals (p = 0.073), their tobacco smoking habits (p = 0.048), and their use of firewood (p = 0.002) emerged as potential correlates of LFI. We also added age and sex, which act as powerful confounders in most human analyses.

After adjusting for other variables, the independent predictors of LFI (aOR, 95% CI; p-value) are: working in the informal sector [3.0 (1.2 – 8.8); 0.028], smoking [3.6 (1.2 – 11.1); 0.021] and using firewood [17.7 (3.0 – 336.9); 0.008] (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this research was to determine factors linked to lung function impaired (LFI) among people who have previously suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis. Our study found that approximately one-third 31.9% of patients treated for pulmonary tuberculosis had persistent impairment of lung function assessed by spirometry after treatment. Among them, 58.1% had mild form, 37.2% moderate form and 4.6% severe form. In terms of patterns, 91.9% had an obstructive pattern, 0.7% had a restrictive pattern, and 7.4% a mixed pattern. Regarding the associated factors of LFI, we found that current smoker [aOR:3.6; CI 95%:1.2-11.1; p=0.021], the use of biomass fuels [aOR:17.7; CI 95%:3.0–336.9; p=0.008] and work in the informal sector [aOR:3.0; CI 95%:1.2–8.8; p= 0.028] are all significantly associated with LFI.

Our results regarding current smoker as a factor favoring the occurrence of LFI in people with a history of pulmonary TB align with those of Ramos et al. [11]. Several possible explanations exist for this finding. For starters, smoking cigarettes, which is an unhealthy behavior, substantially contributes to the incidence and progression of tuberculosis. This condition causes chronic airflow limitation, which worsens when it recurs [11]. Smoking has harmful effects on a parenchyma already weakened by tuberculosis infection. Moreover, individuals who smoke often engage in other unhealthy habits, such as excessive alcohol consumption, which increases their susceptibility to infections like recurring bacterial pneumonia. These infections can negatively impact lung function. Working in the informal sector increases the risk of impaired lung function, which could be explained by prolonged occupational exposure to inhaled pollutants (dust, fumes) in the absence of adequate respiratory protection. The informal sector may reflect socioeconomic vulnerability, a delay in diagnosis or limited access to healthcare. Interestingly, the use of wood as fuel emerged as a significant predictor of LFI, with the highest adjusted odds ratio among the three factors. Which could explain the more deleterious role of domestic pollutants from biomass compared to smoking. This finding is consistent with an earlier one on the same population, which found that biomass fuels were more strongly linked to COPD than smoking or a history of asthma [12]. Our study was the first in sub–Saharan Africa to investigate post-tuberculosis LFI in the community setting. The use of spirometry according to international standards (GLI, ATS/ERS) to objectify functional anomalies was an asset. We designed our large, multi-site and rigorous sampling to ensure valid data and representative results. Despite these strengths, our study did face some limitations, particularly regarding the size of our sample. A bigger group would have allowed us to uncover additional correlating factors and enhance the potency of our findings. Another weakness is the lack of documented medical data. Participants may forget or fail to mention certain conditions, which leads to their underestimation. The results of this study support strengthening respiratory function monitoring for patients cured of tuberculosis through the systematic implementation of spirometry testing at the end of treatment. Other actions include post-tuberculosis smoking cessation campaigns, promoting alternatives to solid fuels, and improving working conditions in the informal sector.

CONCLUSION

Among these adults with successfully treated PTB, LFI was frequent in Cameroon, and it was mainly mild to moderate. Factors that contributed to this condition included current smoking habits, employment in the informal sector, and reliance on wood for cooking.

Acknowledgement:

Data acquisition, data interpretation: Ngadi Patience, Massongo Massongo, Ngah Komo Elisabeth

Writing the article: Ngah Komo Elisabeth, Massongo Massongo, Ntyo’o Nkoumou Arnaud

Final approval of the version to be corrected: Kuaban Alain, Amadou Dodo Balkissou, Poka- Mayap Virginie, Endale Mireille, Nsounfon Abdou, Pefura Yone Eric

REFERENCES

FIGURES - TABLES

REFERENCES

ARTICLE INFO DOI: 10.12699/jfvpulm.17.51.2026.49

Conflict of Interest

Non

Date of manuscript receiving

10/9/2025

Date of publication after correction

25/11/2025

Article citation

Ngah Komo Marie Elisabeth, Massongo Massongo, Ntyo’o-Nkoumou Arnaud, Amadou Dodo Balkissou, Kuaban Alain, Nsounfon Abdou, Poka - Mayap Virginie, Ngadi Patience, Endale Mireille, Pefura - Yone Eric Walter. Factors associated with lung function impairment in subjects with past history of drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis in Cameroon. J Fran Vent PulmS 2026;51(17):55-60