English

English

French

French

Circadian rhythm disruption in the intensive care unit and its impact on post-intensive care recovery: a narrative review

Perturbation du rythme circadien en unité de soins intensifs et son impact sur la récupération post-réanimation : une revue narrative

Tien Nguyen-Quang1, Dung Ho-Quoc1, Thang Thai-Nguyen-Minh1, Sy Duong-Quy2,3,4,5

1Intensive Care Unit, Binh Duong General Hospital, Vietnam

2Sleep Medicine Research Center. Vietnam Society of Sleep Medicine. Lam Dong, Viet Nam

3Bio-Medical Research Center. Lam Dong Medical College of Medicine. Lam Dong, Vietnam

4Penn State College of Medicine, Penn State University. Pennsylvania, United States

5Sleep Medicine Department. University of Medicine and Pharmacy. Hanoi National University. Hanoi, Vietnam

Corresponding author: Sy Duong-Quy. Sleep Medicine Research Center. Vietnam Society of Sleep Medicine. Lam Dong, Viet Nam.

ABSTRACT

Circadian rhythm disruption and sleep–wake disturbances are common yet underrecognized consequences of critical illness, with important implications for neurological recovery, ventilator liberation, and long-term outcomes after intensive care unit (ICU) discharge. This general review summarizes current knowledge on how ICU-related pharmacological exposures, mechanical ventilation, and environmental factors interact to induce circadian disruption at behavioral, physiological, and molecular levels. Existing evidence indicates that commonly used sedatives acting on GABAergic pathways markedly suppress restorative sleep stages and abolish normal circadian rhythmicity, whereas dexmedetomidine more closely preserves physiological sleep architecture. In addition, several non-sedative medications frequently administered in the ICU, including opioids, corticosteroids, and melatonin-based agents, modulate circadian regulation through distinct neuroendocrine and respiratory mechanisms. Mechanical ventilation further contributes to sleep fragmentation through patient–ventilator asynchrony and mode-dependent over-assistance, while experimental studies demonstrate circadian-dependent vulnerability to ventilator-induced lung injury mediated by core clock genes such as BMAL1. Environmental factors in the ICU, notably abnormal light–dark exposure, excessive noise, and frequent care activities, disrupt external zeitgebers and alter melatonin and cortisol secretion. These disturbances may persist after ICU discharge as part of post-intensive care syndrome (SLEEP–WAKE). Emerging chronobiology-informed strategies, including circadian-preserving pharmacological approaches, adaptive ventilatory modes, environmental optimization, and targeted chronotherapy, represent promising directions to improve recovery in critically ill patients.

KEYWORDS: ICU; Sleep disruption; Circadian rhythms; Mechanical ventilation; Chronotherapy.

RÉSUMÉ

La perturbation du rythme circadien et les troubles du cycle veille–sommeil constituent des conséquences fréquentes mais encore sous-reconnues des maladies critiques, avec des implications majeures pour la récupération neurologique, le sevrage de la ventilation mécanique et les résultats à long terme après la sortie de l’unité de soins intensifs (USI). Cette revue générale synthétise les connaissances actuelles sur la manière dont les expositions pharmacologiques propres à l’USI, la ventilation mécanique et les facteurs environnementaux interagissent pour induire une désorganisation circadienne aux niveaux comportemental, physiologique et moléculaire. Les données disponibles indiquent que les sédatifs couramment utilisés, agissant sur les voies GABAergiques, suppriment fortement les stades de sommeil réparateur et abolissent la rythmicité circadienne normale, tandis que la dexmédétomidine préserve davantage l’architecture physiologique du sommeil. Par ailleurs, plusieurs médicaments non sédatifs fréquemment administrés en USI, notamment les opioïdes, les corticostéroïdes et les agents à base de mélatonine, modulent la régulation circadienne par des mécanismes neuroendocriniens et respiratoires distincts. La ventilation mécanique contribue également à la fragmentation du sommeil par l’asynchronie patient–ventilateur et une assistance excessive dépendante du mode ventilatoire, tandis que des études expérimentales montrent une vulnérabilité dépendante du rythme circadien aux lésions pulmonaires induites par la ventilation, médiée par des gènes clés de l’horloge biologique tels que BMAL1. Les facteurs environnementaux en USI, notamment l’exposition anormale aux cycles lumière–obscurité, le bruit excessif et la fréquence élevée des soins, perturbent les synchroniseurs externes (zeitgebers) et modifient la sécrétion de mélatonine et de cortisol. Ces perturbations peuvent persister après la sortie de l’USI dans le cadre du syndrome post-soins intensifs (SLEEP–WAKE). Des stratégies émergentes fondées sur la chronobiologie, incluant des approches pharmacologiques respectant le rythme circadien, des modes ventilatoires adaptatifs, l’optimisation de l’environnement et une chronothérapie ciblée, représentent des pistes prometteuses pour améliorer la récupération des patients en état critique.

MOTS CLÉS: USI; Perturbation du sommeil; Rythme circadian; Ventilation mécanique; Chronothérapie.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent among critically ill patients and are increasingly recognized as a major determinant of both short- and long-term outcomes following intensive care unit (ICU) admission [1]. Beyond environmental noise and procedural interruptions, ICU-related sleep disruption reflects profound alterations in circadian regulation, sleep architecture, and neurophysiological homeostasis. These disturbances have been consistently associated with delirium, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and SLEEP–WAKE, underscoring their clinical relevance beyond the acute phase of critical illness [2,3].

Despite growing awareness, sleep in the ICU has traditionally been regarded as an unavoidable consequence of severe illness rather than a therapeutic target (Figure 1). In this context, ICU sleep disruption is not merely a symptom of critical illness, but a modifiable pathophysiological target. This narrative review synthesizes current evidence on the physiological mechanisms, pharmacological influences, and ventilatory factors contributing to sleep and circadian disruption in critically ill patients, while highlighting emerging chronobiology-informed strategies for clinical practice.

Circadian Rhythms and Critical Illness

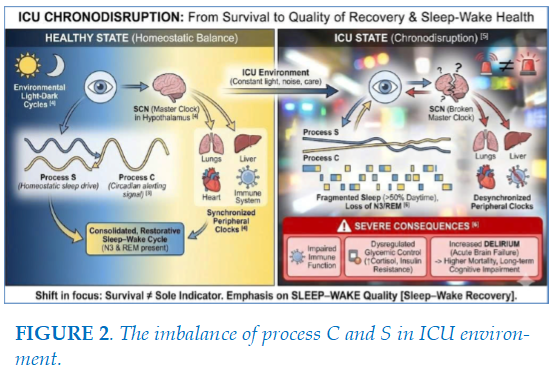

Survival among intensive care unit (ICU) patients is no longer regarded as the sole indicator of therapeutic success; increasing attention has shifted toward the quality of functional and psychological recovery following critical illness, collectively referred to as SLEEP–WAKE. Circadian rhythms are endogenous regulatory systems with an approximately 24-hour cycle, coordinating physiological processes, behaviors, and metabolism to adapt to environmental light-dark cycles [4]. This coordinating center, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, functions as a "master clock" that receives light signals from the retina to synchronize "peripheral clocks" in organs such as the lungs, liver, heart, and immune system [4]. Under homeostatic conditions, circadian rhythms maintain the balance between sleep and wakefulness

through the interaction of the homeostatic process (Process S) and the circadian process (Process C) [3] (Figure 2). In the intensive care unit (ICU), patients confront a condition scientists term "chronodisruption" [5]. This is not merely sleep deprivation but a total collapse of the endogenous timekeeping system. 24-hour polysomnography (PSG) studies demonstrate that ICU sleep architecture is extremely fragmented, with over 50% of sleep occurring during daytime hours, and restorative stages such as slow-wave sleep (N3) or REM sleep are frequently diminished or entirely absent [6]. This disruption leads to severe biological consequences: impaired immune function, dysregulated glycemic control via insulin resistance induced by elevated cortisol, and notably, an increased risk of delirium—an acute brain failure linked to higher mortality rates and long-term cognitive impairment [6].

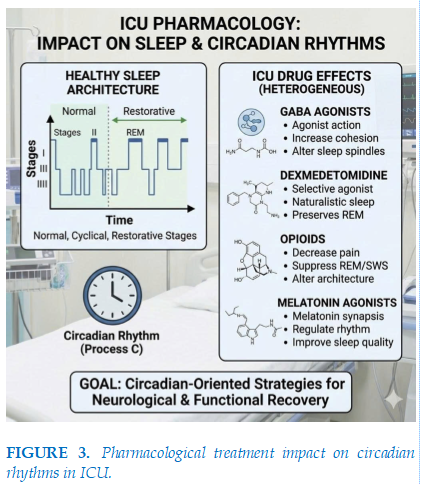

Pharmacological Determinants of Sleep and Circadian Disruption in the ICU (Figure 3)

Pharmacological agents commonly used in the ICU, including sedatives, analgesics, and other neuroactive medications, play a central role in facilitating patient comfort and tolerance of life-sustaining interventions such as mechanical ventilation. However, accumulating evidence indicates that many of these agents exert heterogeneous—and often adverse—effects on sleep architecture and circadian regulation, with important implications for neurological and functional recovery [2,3]. These effects are not uniform and depend on whether agents suppress, mimic, or attempt to restore physiological sleep–wake regulation. GABA Agonists: Propofol and Benzodiazepines (such as midazolam) function by stimulating gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, inducing a potent state of central nervous system depression [1]. Although patients appear to be sleeping, electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings reveal a state more akin to anesthesia than natural sleep. Specifically, these agents severely suppress REM and slow-wave sleep (SWS/N3) [1]. A pharmacokinetic study of prolonged propofol infusion in the ICU found no day-night variation in metabolic concentrations, and the bispectral index (BIS)—a measure of sedation depth—similarly lost its rhythmicity [7]. This implies the drug effectively erases the day-night boundary within the patient's brain. Prolonged propofol infusion abolishes normal day–night variability in electroencephalographic and pharmacodynamic markers, reflecting a loss of circadian modulation of central nervous system activity [7]. Dexmedetomidine is a selective α2-adrenergic agonist at the locus coeruleus, functioning by inhibiting norepinephrine release, thereby activating natural sleep-inducing pathways in the brainstem [8]. Unlike propofol, dexmedetomidine induces a sedative state where patients remain easily rousable to interact with medical staff [8]. Direct comparative studies have demonstrated that dexmedetomidine increases sleep efficiency, enhances N2 sleep stages, and preserves a portion of REM sleep compared to other drug classes [9]. More critically, utilizing dexmedetomidine over benzodiazepines is associated with a significant reduction in delirium incidence and shorter mechanical ventilation duration [10]. Melatonin receptor agonists have been shown to reduce delirium incidence and ICU length of stay without causing respiratory depression.

Opioids, including fentanyl and morphine, disrupt the sleep–wake cycle primarily through activation of μ-opioid receptors (MORs) within brainstem respiratory centers, such as the pre-Bötzinger complex, thereby predisposing patients to central sleep apnea (CSA). These agents markedly reduce restorative sleep stages, including slow-wave sleep (SWS/N3) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, while concomitantly increasing lighter N2 sleep. Importantly, a bidirectional and self-perpetuating relationship has been described, whereby opioid-induced sleep disruption exacerbates pain sensitivity, leading to escalating analgesic requirements and further deterioration of sleep quality. Beyond sleep disruption, opioids exacerbate central sleep apnea and upper airway collapsibility, thereby impairing nocturnal respiration and potentially complicating liberation from mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients [11].

Exogenous melatonin plays a key role in resynchronizing the sleep–wake cycle through its direct influence on the circadian process (Process C). Ramelteon, a selective MT₁/MT₂ melatonin receptor agonist, has been shown in clinical trials to significantly reduce delirium incidence in ICU patients (24.4% versus 46.5% in placebo groups) while shortening ICU length of stay [12, 13]. Importantly, melatonin-based therapies do not induce respiratory depression and may confer neuroprotective effects, positioning them as promising agents within circadian-oriented therapeutic strategies in critical care [12].

Corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone and dexamethasone, are well-recognized contributors to insomnia, affecting approximately 70% of treated patients. EEG-based studies have demonstrated that high-dose steroid pulse therapy (SPT) profoundly suppresses REM sleep, with dramatic reductions in REM duration (e.g., from 71.2 minutes to 9.4 minutes) [14,15]. Underlying mechanisms include disruption of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, suppression of nocturnal melatonin secretion, and sustained hyperarousal, collectively increasing the risk of delirium and persistent sleep disturbances following critical illness [14].

Ketamine, via NMDA receptor antagonism, induces a dissociative sedative state characterized by REM sleep reduction and increased sleep fragmentation, particularly at higher doses [16]. Among antipsychotics, quetiapine has been associated with improved nocturnal sleep duration and shorter ICU stays in patients with hyperactive delirium, outperforming haloperidol in several comparative studies [17]. Volatile anesthetics such as isoflurane and sevoflurane, when employed for ICU sedation, have been shown to facilitate faster awakening and earlier extubation compared with intravenous sedatives, although the resulting EEG patterns more closely resemble anesthesia than physiological sleep [18].

Mechanical Ventilation and Circadian Interaction

The relationship between mechanical ventilation and circadian rhythms extends beyond sleep fragmentation caused by physical discomfort, reaching into molecular mechanisms and pulmonary pathobiology (Figure 4) [19].

Ventilated patients experience frequent awakenings due to patient-ventilator asynchrony—a mismatch between their respiratory effort and the machine's cycle [20]. Factors such as endotracheal tube discomfort, excessive airway pressure, or inappropriate trigger settings induce brief awakenings, shattering continuous sleep architecture [21]. The co administration of opioids and sedatives to facilitate ventilator tolerance carries the side effect of increasing central apnea risk and upper airway collapsibility, particularly in patients with pre-existing obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [11].

One of the most significant discoveries in modern critical care is that the severity of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) fluctuates according to the time of day [19]. Animal models demonstrate that initiating mechanical ventilation at "dawn" (the onset of the rest phase) causes more severe neutrophil infiltration, increased alveolar permeability, and reduced lung compliance compared to initiation at "dusk" [22].

The molecular mechanism underlying this phenomenon involves the BMAL1 clock gene in myeloid cells. BMAL1 regulates leukocyte trafficking and inflammatory responses through chemotactic pathways [22]. When this gene is deficient, the rhythmicity of lung injury vanishes, proving that endogenous molecular clocks dictate the resilience of lung parenchyma to mechanical stretch forces from the ventilator [22]. This has introduced the concept of "chronoventilation"—adjusting mechanical ventilation strategies based on circadian rhythms to minimize injury [19].

The choice of ventilatory mode further interacts with circadian physiology by influencing nocturnal respiratory drive and sleep stability. Ventilatory strategies that fail to adapt to circadian reductions in respiratory demand may result in nocturnal over-assistance, promoting central apnea, sleep fragmentation, and loss of restorative sleep stages [3,23]. In contrast, patient-adaptive modes that continuously match ventilatory support to intrinsic respiratory effort improve patient–ventilator synchrony and preserve sleep continuity, particularly during the night [3].

Importantly, the phenomenon of “atypical sleep”, characterized by the loss of classical EEG markers of N2 and N3 sleep, is increasingly observed in patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation [2]. This pattern reflects profound disruption of sleep regulation and carries significant clinical implications.

The absence of restorative sleep stages, particularly REM and N3 sleep, has been directly linked to prolonged ventilator weaning and a higher risk of failure during spontaneous breathing trials (SBTs) [2].

The ICU Environment: Disruptors of Temporal Cues

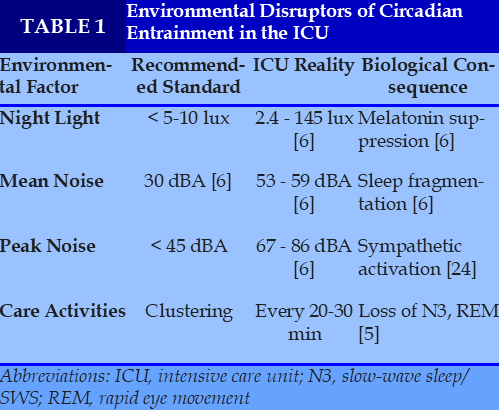

The ICU environment represents a biological paradox: insufficient light exposure during daytime contrasted with excessive illumination at night, combined with persistent background noise [6]. Such conditions profoundly disrupt external time cues (zeitgebers) that are essential for circadian entrainment. To illustrate how ICU environmental conditions deviate from established circadian-friendly standards, Table 1 contrasts recommended thresholds with real-world ICU measurements and their downstream biological consequences on sleep architecture and circadian alignment. Collectively, these deviations underscore the ICU environment as a potent yet modifiable driver of circadian disruption and sleep fragmentation in critically ill patients.

Light is the most powerful zeitgeber (time cue) for synchronizing circadian rhythms. In the ICU, inadequate daytime light exposure fails to promote normal circadian alerting signals, while nocturnal exposure to artificial illumination during routine care activities suppresses endogenous melatonin secretion and induces circadian phase delay [6]. Short-wavelength (blue) light exerts the strongest inhibitory effect on melatonin release, inducing circadian phase delay and exacerbating insomnia and sleep–wake misalignment [25].

Excessive environmental noise constitutes another major disruptor of circadian organization. Persistent background noise and intermittent peak sounds not only provoke repeated arousals but also activate the sympathetic nervous system, leading to tachycardia, blood pressure elevation, and impaired cardiovascular recovery. These effects further destabilize sleep continuity and circadian rhythmicity [6,24]. Frequent care-related interruptions constitute one of the most potent yet modifiable sources of sleep fragmentation in the ICU. Recurrent nursing and medical activities prevent the consolidation of restorative sleep stages, particularly slow-wave and rapid eye movement sleep [2,26]. Sleep-protective care clustering refers to the deliberate grouping of necessary nursing and medical interventions into predefined time blocks, thereby creating uninterrupted sleep windows, especially during nocturnal hours. Studies employing polysomnography and actigraphy have demonstrated that care clustering is associated with fewer nocturnal awakenings, improved sleep efficiency, preservation of N3 and REM sleep, and a reduced incidence of ICU delirium [26,27]. Importantly, care clustering does not imply delaying essential clinical interventions but rather optimizing their timing to align with patients’ circadian physiology. When integrated with environmental light modulation and noise reduction strategies, care clustering constitutes a central pillar of chronotherapeutic ICU care [27].

Biomarkers and Molecular Mechanisms of Circadian Disruption

Circadian disruption in the ICU is not merely a subjective sensation but is quantifiable through biomarkers in blood and urine [3]. These biomarkers provide insight into the severity of chronodisruption and its systemic consequences (Figure 5).

Melatonin and its urinary metabolite (6-sulfatoxymelatonin - aMT6s) are the gold standards for assessing circadian rhythms [28]. In ICU patients with septic shock or respiratory failure, aMT6s levels are typically profoundly low and lack the nocturnal peak [29]. Preservation of melatonin rhythmicity has been associated with improved survival and neurological outcomes, whereas complete loss of circadian signaling reflects severe physiological decompensation [29]. Conversely, mean cortisol levels exceeding 212 ng/mL are closely linked to delirium onset, reflecting extreme stress and the loss of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis control [30].

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from ICU patients show marked alterations in the expression of core genes such as CLOCK, BMAL1, PER1, PER2, and CRY1 [31]. This disruption correlates by over 90% with physiological disturbances like heart rate and blood pressure fluctuations [32]. A key mechanism identified is Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress induced by intermittent hypoxia—a hallmark of OSA and mechanical ventilation. ER stress negatively impacts clock genes, creating a pathological spiral that diminishes cellular resilience.

Collectively, these neuroendocrine and molecular alterations provide a biological substrate linking ICU-related chronodisruption to subsequent sleep–wake disorders, cognitive impairment, and delayed recovery after discharge. Persistence of these abnormalities beyond the acute phase helps explain the high burden of post-ICU circadian dysfunction and highlights the rationale for targeted chronotherapeutic strategies during early recovery.

Post-ICU consequences and chronotherapeutic strategies

As patients transition out of the ICU, restoration of circadian organization often remains incomplete. This is a core component of sleep–wake, impacting both physical and mental health [33]. Longitudinal studies consistently demonstrate a high burden of sleep–wake disturbances following ICU discharge, with gradual improvement over time but persistent symptoms in a substantial subset of survivors [20]. Poor sleep quality and sleep fragmentation are highly prevalent during the first months after discharge and may persist beyond one year, frequently in association with comorbid psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder[33].

There is a robust correlation between poor sleep in the first week post-discharge and cognitive decline. Patients with severe sleep fragmentation (repetitive awakenings) exhibit lower scores in memory and information processing tests. These findings suggest that the early post-discharge period represents a critical window of opportunity for neuroprotection through sleep and circadian optimization.

The ICU's impact on circadian rhythms is further complicated in patients with pre-existing chronic respiratory disorders such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). In asthma and COPD patients, symptoms typically worsen at night due to natural circadian shifts, such as decreased cortisol levels and increased parasympathetic activity inducing bronchoconstriction. In the ICU, environmental chronodisruption amplifies these exacerbations. COPD-OSA patients (overlap syndrome) face a higher risk of severe nocturnal hypoxemia, which exacerbates pulmonary hypertension (PH) via hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction mechanisms. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a significant yet frequently overlooked risk factor in the ICU. OSA patients are prone to upper airway collapse under sedation, increasing airway resistance and hindering ventilator weaning [11]. Implementing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or mandibular devices post-extubation is essential to stabilize the sleep–wake rhythm and prevent residual cardiovascular events. To accurately assess the recovery of circadian rhythms following critical illness, a combination of objective and subjective assessment tools is required. Polysomnography (PSG) is considered the gold standard for determining sleep architecture, including sleep stage classification and the detection of respiratory events. However, routine implementation of PSG in the ICU setting is highly challenging due to the complexity of electrode placement, extensive wiring, and significant signal interference from life-support and monitoring devices [34]. Moreover, conventional sleep scoring criteria are often difficult to apply in critically ill patients because of atypical electroencephalographic patterns. This limitation arises from the frequent presence of atypical electroencephalographic (EEG) patterns, such as the absence of sleep spindles or K-complexes, which compromises accurate sleep staging [3]. During the post-ICU recovery phase, actigraphy represents an invaluable assessment tool. Actigraphy involves a wrist-worn device that continuously records motor activity over extended periods, allowing estimation of total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and sleep fragmentation in real-life environments. When combined with sleep diaries, actigraphy enables clinicians to identify common circadian rhythm disturbances, such as Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome and Irregular Sleep–Wake Rhythm, which are frequently observed among ICU survivors [35]. Chronotherapy is emerging as a promising avenue to shorten treatment duration and improve post-ICU quality of life [36]. Environmental chronotherapeutic interventions, including dynamic light exposure that mimics natural solar cycles, aim to restore physiological melatonin rhythms and reinforce circadian entrainment. Multimodal bundles incorporating nocturnal noise reduction, sleep-protective clustering of care activities, and minimization of alarm burden further enhance sleep continuity and circadian alignment [33,35,37]. Enteral melatonin administration (3-10 mg) at 21:00 has demonstrated efficacy in enhancing sleep efficiency and lowering delirium risk in weaning patients [38]. Melatonin facilitates not only sleep–wake realignment but also exerts antioxidant and pulmonary protective effects, mitigating inflammatory damage within the ICU [39]. Post-discharge, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and nurse-led collaborative care have proved effective in improving long-term sleep scores at 12 months [33]. The use of melatonin measurement to follow-up the circadian rhythms and the use of self-administered home sleep testing to screen sleep-related breathing disorder might be useful [40,41]. Educating patients on sleep hygiene and maintaining consistent sleep–wake schedules is key to "retraining" the damaged biological clock.

Conclusion and Recommendations for Clinical Practice

Circadian rhythm disruption in critically ill patients represents a pervasive yet underrecognized pathophysiological process that extends beyond sleep deprivation to involve neuroendocrine, molecular, and systemic dysregulation. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that ICU-related factors—including pharmacological sedation, mechanical ventilation, and environmental disturbances—converge to impair circadian organization at behavioral, physiological, and cellular levels. These alterations contribute to delirium, prolonged ventilator dependence, and long-term cognitive and functional sequelae after ICU discharge. Importantly, circadian disruption is not merely an epiphenomenon of critical illness but a quantifiable and potentially modifiable therapeutic target. Biomarkers such as melatonin rhythmicity, cortisol dynamics, and clock gene expression provide mechanistic insight into the severity of chronodisruption and help explain the persistence of sleep–wake disturbances and delayed recovery observed in ICU survivors. Recognition of these biological underpinnings underscores the need to integrate circadian considerations into routine critical care practice; especially, the lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic should be awareness by emerging countries such as in Vietnam [42-45]. Chronobiology-informed strategies—including circadian-preserving sedation, patient-adaptive ventilatory support, environmental optimization, and targeted chronotherapy—offer promising avenues to mitigate acute brain dysfunction and support post-ICU recovery. Future research should focus on translating biomarker-based insights into pragmatic bedside tools and validating circadian-oriented interventions that can be feasibly implemented across diverse ICU settings. Protecting circadian integrity may ultimately represent a key step toward improving not only survival, but also the quality of long-term recovery after critical illness.

REFERENCES

| 1. Tronstad, O. and J.F. Fraser, Sleep in the ICU - A complex challenge requiring multifactorial solutions. Crit Care Resusc, 2025. 27(1): p. 100097. |

| 2. Dres, M., et al., Sleep and Pathological Wakefulness at the Time of Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation (SLEEWE). A Prospective Multicenter Physiological Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2019. 199(9): p. 1106-1115. |

| 3. Pisani, M.A., et al., Sleep in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2015. 191(7): p. 731-8. |

| 4. Chan, M.C., et al., Circadian rhythms: from basic mechanisms to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med, 2012. 40(1): p. 246-53. |

| 5. Felten, M., et al., Circadian rhythm disruption in critically ill patients. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 2023. 238(1): p. e13962. |

| 6. Telias, I. and M.E. Wilcox, Sleep and Circadian Rhythm in Critical Illness. Crit Care, 2019. 23(1): p. 82. |

| 7. Bienert, A., et al., Assessing circadian rhythms in propofol PK and PD during prolonged infusion in ICU patients. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn, 2010. 37(3): p. 289-304. |

| 8. Oxlund, J., et al., Dexmedetomidine and sleep quality in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: study protocol for a randomised placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open, 2022. 12(3): p. e050282. |

| 9. Nasihuddin, N., Dexmedetomidine Versus Propofol for ICU Sedation: Long-Term Cognitive and Cardiovascular Outcomes. 2025. 17(6): p. 94-97. |

| 10. Heybati, K., et al., Outcomes of dexmedetomidine versus propofol sedation in critically ill adults requiring mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth, 2022. 129(4): p. 515-526. |

| 11. Locihová, H., et al., Effect of sleep quality on weaning from mechanical ventilation: A scoping review. J Crit Care Med (Targu Mures), 2025. 11(1): p. 23-32. |

| 12. Hatta, K., et al., Preventive effects of ramelteon on delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 2014. 71(4): p. 397-403. |

| 13. Mukundarajan, R., K.D. Soni, and A. Trikha, Prophylactic Melatonin for Delirium in Intensive Care Unit: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Indian J Crit Care Med, 2023. 27(9): p. 675-685. |

| 14. Born, J. and H.L. Fehm, The neuroendocrine recovery function of sleep. Noise Health, 2000. 2(7): p. 25-38. |

| 15. Van Marle, H.J., et al., The effect of exogenous cortisol during sleep on the behavioral and neural correlates of emotional memory consolidation in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2013. 38(9): p. 1639-49. |

| 16. Duncan, W.C., Jr. and C.A. Zarate, Jr., Ketamine, sleep, and depression: current status and new questions. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2013. 15(9): p. 394. |

| 17. Devlin, J.W., et al., Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med, 2010. 38(2): p. 419-27. |

| 18. Mesnil, M., et al., Long-term sedation in intensive care unit: a randomized comparison between inhaled sevoflurane and intravenous propofol or midazolam. Intensive Care Med, 2011. 37(6): p. 933-41. |

| 19. Wilcox, M.E. and M.B. Maas, Beating the Clock in Ventilator-induced Lung Injury. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2023. 207(11): p. 1415-1416. |

| 20. Showler, L., et al., Sleep during and following critical illness: A narrative review. World J Crit Care Med, 2023. 12(3): p. 92-115. |

| 21. Erbay Dalli, Ö. and N. Kelebek Girgin, Sleep Quality and Disruptive Factors in Intensive Care Units: A Comparison Between Mechanically Ventilated and Spontaneously Breathing Patients. Nurs Crit Care, 2025. 30(4): p. e70097. |

| 22. Felten, M., et al., Ventilator-induced Lung Injury Is Modulated by the Circadian Clock. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2023. 207(11): p. 1464-1474. |

| 23. Delisle, S., et al., Sleep quality in mechanically ventilated patients: comparison between NAVA and PSV modes. Ann Intensive Care, 2011. 1(1): p. 42. |

| 24. Daou, M., et al., Abnormal Sleep, Circadian Rhythm Disruption, and Delirium in the ICU: Are They Related? Frontiers in Neurology, 2020. Volume 11 - 2020. |

| 25. Eschbach, E. and J. Wang, Sleep and critical illness: a review. Frontiers in Medicine, 2023. Volume 10 - 2023. |

| 26. Elliott, R., et al., Characterisation of sleep in intensive care using 24-hour polysomnography: an observational study. Crit Care, 2013. 17(2): p. R46. |

| 27. Devlin, J.W., et al., Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med, 2018. 46(9): p. e825-e873 |

| 28. Fishbein, A.B., K.L. Knutson, and P.C. Zee, Circadian disruption and human health. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2021. 131(19). |

| 29. Melone, M.A., et al., Disruption of the circadian rhythm of melatonin: A biomarker of critical illness severity. Sleep Med, 2023. 110: p. 60-67. |

| 30. Sun, T., et al., Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances in intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired delirium: a case-control study. J Int Med Res, 2021. 49(3): p. 300060521990502. |

| 31. Sundar, I.K., et al., Circadian molecular clock in lung pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2015. 309(10): p. L1056-75. |

| 32. Jiménez-Pastor, J.M., et al., Interaction between clock genes, melatonin and cardiovascular outcomes from ICU patients. Intensive Care Med Exp, 2025. 13(1): p. 19. |

| 33. Fukamachi, Y., et al., Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Intervention of Long-Term Sleep Disturbance After Intensive Care Unit Discharge: A Scoping Review. Cureus, 2025. 17(4): p. e83011. |

| 34. Knauert, M.P., et al., Causes, Consequences, and Treatments of Sleep and Circadian Disruption in the ICU: An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2023. 207(7): p. e49-e68. |

| 35. Schmidt, B., The Effects of Sleep Disturbances on Patients in the Intensive Care Setting. 2021. |

| 36. Xovier, C., Chronotherapy as a Restorative Strategy for Disrupted Sleep Wake Cycles: Clinical Insights and Applications. Journal of Sleep Disorders & Therapy, 2025. 14: p. 650. |

| 37. Zhang, Y., et al., Based -evidence, an intervention study to improve sleep quality in awake adult ICU patients: a prospective, single-blind, clustered controlled trial. Crit Care, 2024. 28(1): p. 365. |

| 38. Luther, R. and A. McLeod, The effect of chronotherapy on delirium in critical care - a systematic review. Nurs Crit Care, 2018. 23(6): p. 283-290. |

| 39. Tang, B.H.Y., et al., Melatonin Use in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med, 2025. 53(9): p. e1714-e1724. |

| 40. Bui-Diem, K., Van Tho, N., Nguyen-Binh, T., Doan-Truc, Q., Trinh, H. K. T., Truong, D. D., ... & Duong-Quy, S. (2025). Melatonin and Cortisol Concentration Before and After CPAP Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Nature and Science of Sleep, 2201-2212. |

| 41. Duong-Quy, S., Nguyen-Duy, T., Hoc, T. V., Nguyen-Thi-Hong, L., Tang-Thi-Thao, T., Bui-Diem, K., ... & Penzel, T. Self-administered home sleep testing model in screening of OSA in healthcare workers—SOHEW study: a national multicenter study in Vietnam. Pulmonary Therapy, 2025;11(4), 625-643. |

| 42. Duong-Quy, S., Tang-Thi-Thao, T., Huynh-Truong-Anh, D., Hoang-Thi-Xuan, H., Nguyen-Van, T., Nguyen-Tuan, A., ... & Nguyen-Duy, T. Sleep disorders in patients with severe COVID-19 treated in the intensive care unit: a real-life descriptive study in Vietnam. Discov Med, 2024;36(183), 690-8. |

| 43. Duong-Quy, S., Nguyen-Van, T., Nguyen-Tuan, A., Tang-Thi-Thao, T., Nguyen-Hoang, Q., Tran-Van, H., & Vo-Thi-Kim, A. The Impact of Acute COVID-19 Infection on Sleep Disorders: A Real-life Descriptive Study during the Outbreak of COVID-19 Pandemic in Vietnam. Current Respiratory Medicine Reviews, 2023;19(4), 289-295. |

| 44. Duong-Quy, S., Huynh-Truong-Anh, D., Nguyen-Thi-Kim, T., Nguyen-Quang, T., Tran-Ngoc-Anh, T., Nguyen-Van-Hoai, N., ... & Nguyen-Duy, T. Predictive factors of mortality in patients with severe COVID-19 treated in the intensive care unit: a single-center study in Vietnam. Pulmonary therapy, 2023;9(3), 377-394. |

| 45. Duong‐Quy, S. Letter From the Vietnam Respiratory Society—Vietnam's Respiratory Medicine in Transition: From Clinical Advances to National Healthcare Policy. Respirology 2025. |

FIGURES - TABLES

REFERENCES

| 1. Tronstad, O. and J.F. Fraser, Sleep in the ICU - A complex challenge requiring multifactorial solutions. Crit Care Resusc, 2025. 27(1): p. 100097. |

| 2. Dres, M., et al., Sleep and Pathological Wakefulness at the Time of Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation (SLEEWE). A Prospective Multicenter Physiological Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2019. 199(9): p. 1106-1115. |

| 3. Pisani, M.A., et al., Sleep in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2015. 191(7): p. 731-8. |

| 4. Chan, M.C., et al., Circadian rhythms: from basic mechanisms to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med, 2012. 40(1): p. 246-53. |

| 5. Felten, M., et al., Circadian rhythm disruption in critically ill patients. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 2023. 238(1): p. e13962. |

| 6. Telias, I. and M.E. Wilcox, Sleep and Circadian Rhythm in Critical Illness. Crit Care, 2019. 23(1): p. 82. |

| 7. Bienert, A., et al., Assessing circadian rhythms in propofol PK and PD during prolonged infusion in ICU patients. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn, 2010. 37(3): p. 289-304. |

| 8. Oxlund, J., et al., Dexmedetomidine and sleep quality in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: study protocol for a randomised placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open, 2022. 12(3): p. e050282. |

| 9. Nasihuddin, N., Dexmedetomidine Versus Propofol for ICU Sedation: Long-Term Cognitive and Cardiovascular Outcomes. 2025. 17(6): p. 94-97. |

| 10. Heybati, K., et al., Outcomes of dexmedetomidine versus propofol sedation in critically ill adults requiring mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth, 2022. 129(4): p. 515-526. |

| 11. Locihová, H., et al., Effect of sleep quality on weaning from mechanical ventilation: A scoping review. J Crit Care Med (Targu Mures), 2025. 11(1): p. 23-32. |

| 12. Hatta, K., et al., Preventive effects of ramelteon on delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 2014. 71(4): p. 397-403. |

| 13. Mukundarajan, R., K.D. Soni, and A. Trikha, Prophylactic Melatonin for Delirium in Intensive Care Unit: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Indian J Crit Care Med, 2023. 27(9): p. 675-685. |

| 14. Born, J. and H.L. Fehm, The neuroendocrine recovery function of sleep. Noise Health, 2000. 2(7): p. 25-38. |

| 15. Van Marle, H.J., et al., The effect of exogenous cortisol during sleep on the behavioral and neural correlates of emotional memory consolidation in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2013. 38(9): p. 1639-49. |

| 16. Duncan, W.C., Jr. and C.A. Zarate, Jr., Ketamine, sleep, and depression: current status and new questions. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2013. 15(9): p. 394. |

| 17. Devlin, J.W., et al., Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med, 2010. 38(2): p. 419-27. |

| 18. Mesnil, M., et al., Long-term sedation in intensive care unit: a randomized comparison between inhaled sevoflurane and intravenous propofol or midazolam. Intensive Care Med, 2011. 37(6): p. 933-41. |

| 19. Wilcox, M.E. and M.B. Maas, Beating the Clock in Ventilator-induced Lung Injury. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2023. 207(11): p. 1415-1416. |

| 20. Showler, L., et al., Sleep during and following critical illness: A narrative review. World J Crit Care Med, 2023. 12(3): p. 92-115. |

| 21. Erbay Dalli, Ö. and N. Kelebek Girgin, Sleep Quality and Disruptive Factors in Intensive Care Units: A Comparison Between Mechanically Ventilated and Spontaneously Breathing Patients. Nurs Crit Care, 2025. 30(4): p. e70097. |

| 22. Felten, M., et al., Ventilator-induced Lung Injury Is Modulated by the Circadian Clock. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2023. 207(11): p. 1464-1474. |

| 23. Delisle, S., et al., Sleep quality in mechanically ventilated patients: comparison between NAVA and PSV modes. Ann Intensive Care, 2011. 1(1): p. 42. |

| 24. Daou, M., et al., Abnormal Sleep, Circadian Rhythm Disruption, and Delirium in the ICU: Are They Related? Frontiers in Neurology, 2020. Volume 11 - 2020. |

| 25. Eschbach, E. and J. Wang, Sleep and critical illness: a review. Frontiers in Medicine, 2023. Volume 10 - 2023. |

| 26. Elliott, R., et al., Characterisation of sleep in intensive care using 24-hour polysomnography: an observational study. Crit Care, 2013. 17(2): p. R46. |

| 27. Devlin, J.W., et al., Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med, 2018. 46(9): p. e825-e873 |

| 28. Fishbein, A.B., K.L. Knutson, and P.C. Zee, Circadian disruption and human health. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2021. 131(19). |

| 29. Melone, M.A., et al., Disruption of the circadian rhythm of melatonin: A biomarker of critical illness severity. Sleep Med, 2023. 110: p. 60-67. |

| 30. Sun, T., et al., Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances in intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired delirium: a case-control study. J Int Med Res, 2021. 49(3): p. 300060521990502. |

| 31. Sundar, I.K., et al., Circadian molecular clock in lung pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2015. 309(10): p. L1056-75. |

| 32. Jiménez-Pastor, J.M., et al., Interaction between clock genes, melatonin and cardiovascular outcomes from ICU patients. Intensive Care Med Exp, 2025. 13(1): p. 19. |

| 33. Fukamachi, Y., et al., Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Intervention of Long-Term Sleep Disturbance After Intensive Care Unit Discharge: A Scoping Review. Cureus, 2025. 17(4): p. e83011. |

| 34. Knauert, M.P., et al., Causes, Consequences, and Treatments of Sleep and Circadian Disruption in the ICU: An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2023. 207(7): p. e49-e68. |

| 35. Schmidt, B., The Effects of Sleep Disturbances on Patients in the Intensive Care Setting. 2021. |

| 36. Xovier, C., Chronotherapy as a Restorative Strategy for Disrupted Sleep Wake Cycles: Clinical Insights and Applications. Journal of Sleep Disorders & Therapy, 2025. 14: p. 650. |

| 37. Zhang, Y., et al., Based -evidence, an intervention study to improve sleep quality in awake adult ICU patients: a prospective, single-blind, clustered controlled trial. Crit Care, 2024. 28(1): p. 365. |

| 38. Luther, R. and A. McLeod, The effect of chronotherapy on delirium in critical care - a systematic review. Nurs Crit Care, 2018. 23(6): p. 283-290. |

| 39. Tang, B.H.Y., et al., Melatonin Use in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med, 2025. 53(9): p. e1714-e1724. |

| 40. Bui-Diem, K., Van Tho, N., Nguyen-Binh, T., Doan-Truc, Q., Trinh, H. K. T., Truong, D. D., ... & Duong-Quy, S. (2025). Melatonin and Cortisol Concentration Before and After CPAP Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Nature and Science of Sleep, 2201-2212. |

| 41. Duong-Quy, S., Nguyen-Duy, T., Hoc, T. V., Nguyen-Thi-Hong, L., Tang-Thi-Thao, T., Bui-Diem, K., ... & Penzel, T. Self-administered home sleep testing model in screening of OSA in healthcare workers—SOHEW study: a national multicenter study in Vietnam. Pulmonary Therapy, 2025;11(4), 625-643. |

| 42. Duong-Quy, S., Tang-Thi-Thao, T., Huynh-Truong-Anh, D., Hoang-Thi-Xuan, H., Nguyen-Van, T., Nguyen-Tuan, A., ... & Nguyen-Duy, T. Sleep disorders in patients with severe COVID-19 treated in the intensive care unit: a real-life descriptive study in Vietnam. Discov Med, 2024;36(183), 690-8. |

| 43. Duong-Quy, S., Nguyen-Van, T., Nguyen-Tuan, A., Tang-Thi-Thao, T., Nguyen-Hoang, Q., Tran-Van, H., & Vo-Thi-Kim, A. The Impact of Acute COVID-19 Infection on Sleep Disorders: A Real-life Descriptive Study during the Outbreak of COVID-19 Pandemic in Vietnam. Current Respiratory Medicine Reviews, 2023;19(4), 289-295. |

| 44. Duong-Quy, S., Huynh-Truong-Anh, D., Nguyen-Thi-Kim, T., Nguyen-Quang, T., Tran-Ngoc-Anh, T., Nguyen-Van-Hoai, N., ... & Nguyen-Duy, T. Predictive factors of mortality in patients with severe COVID-19 treated in the intensive care unit: a single-center study in Vietnam. Pulmonary therapy, 2023;9(3), 377-394. |

| 45. Duong‐Quy, S. Letter From the Vietnam Respiratory Society—Vietnam's Respiratory Medicine in Transition: From Clinical Advances to National Healthcare Policy. Respirology 2025. |

ARTICLE INFO DOI:10.12699/jfvpulm.17.51.2026.84

Conflict of Interest

Non

Date of manuscript receiving

10/9/2025

Date of publication after correction

26/12/2025

Article citation

Tien Nguyen-Quang, Dung Ho-Quoc, Thang Thai-Nguyen-Minh, Sy Duong-Quy. Circadian rhythm disruption in the intensive care unit and its impact on post-intensive care recovery: a narrative review. J Fran Vent PulmS 2026;51(17):85-93